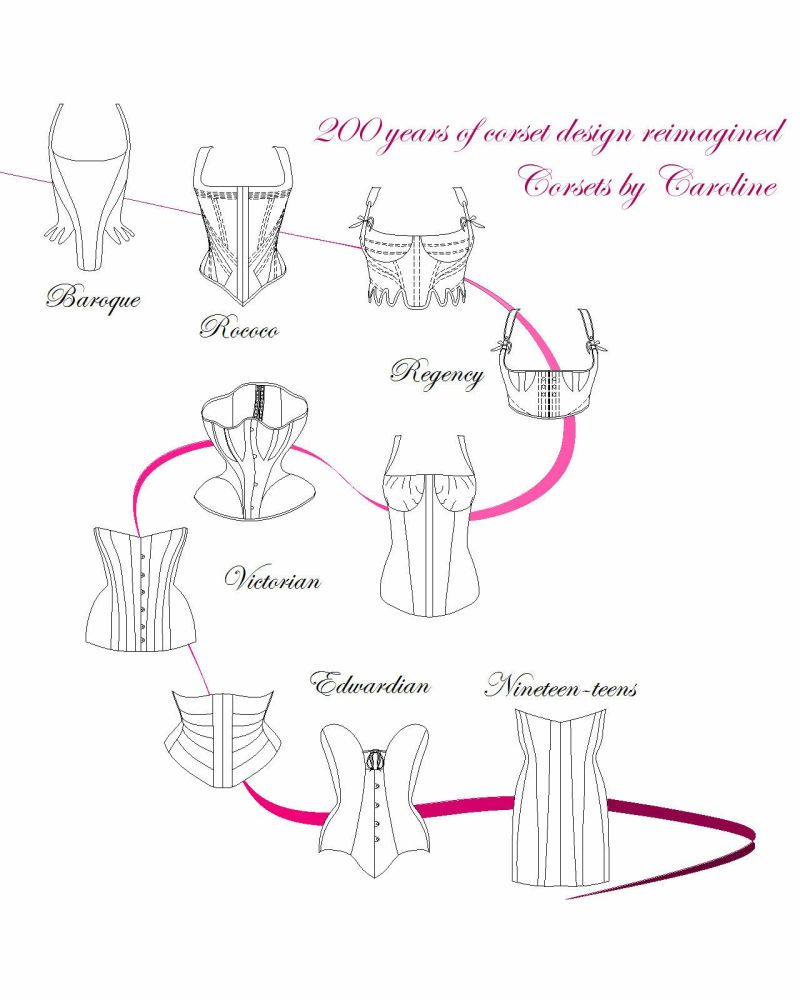

New pattern collection just published - 200 yrs of corset design reimagined

Posted on

I have wanted to do a 200 year timeline of patterns for a while but there was a large gap between my 1715 Stays and the Regency. With the publication of my Rococo stays last week I was able to add the missing link!

This is an extensive value-for-money pattern book (294 pages in total) with ten beautiful patterns to work through - inspiration has been taken from historical examples that have been reimagined for the 21st century maker.

The advantage of having sixty corset designs to my name is that I can, whilst doing a retrospective and curating a collection, pick and choose across all the eras that have inspired me. I have always thought of myself as a modern corset designer, however I realise that the past has inspired me more than I thought.

For this collection I wanted to start with the earliest design I have patterned which are some stays from the early eighteenth century – the Baroque, and finish with one of my favourite patents – the Elizabeth Hume design from the first world war some 200 years later. I have added some historical text to give some background to the eras covered for the simple reason that history is interesting! It also gives some context to the designs – corsets were after all fundamentally about creating the correct underpinnings to shape and support the fashions of the time.

The history of corsets as underpinnings continues to fascinate. Keen corset makers like myself constantly probe and investigate, test ideas, and attempt to unravel the secrets of the past masters. The designs in this E-book are modern versions of historical stays and corsets that I admire and have used for inspiration – the are not exact reproductions. I have been lucky enough to interrogate some extant examples in person such as the Edwardian ‘Sanakor’ corset in the Symington Collection (Leicestershire Museums) but most are interpretations based on Museum photographs or rough patent sketches. I have attempted to preserve the silhouettes but with a juxtaposition of panelling that often does not follow the original designs – the Rococo stays for instance have double the number of panels and the skirts (that would normally splay over the voluminous skirts of the time) are fused and shaped around the hip for the modern wearer.

The eighteenth century

From Baroque to Rococo to Neoclassism – three major aesthetic movements dominated this century. In terms of the artistic styles that were mirrored in the fashions, the Baroque period at the beginning of the century was dark and dramatic; heavy embroidered drapery and ornamental bejewelled stomachers exaggerating elongated conical shaped torsos. By the 1720’s the style had moved away from this oppressive formality to a lighter more delicate style - Rococo. The colour palate was about pastels and took its inspiration from nature - the fashions were a lot more playful with ruffles and lace, and there was a more sensual cut to the gowns. Towards the end of the century a ‘new classism’ inspired by ancient Greece and Rome took hold and is a period much loved by historical fashion enthusiasts. This era was about elegant simplicity – gone was the asymmetry of Rococo, it was now all about balance and a purity of line with a simple colour palate that favoured white and primary shades.

From fully-boned to part boned to not boned very much at-all – the underpinnings changed significantly over the course of this century. In the early years of the century the waist was elongated and the front of the stays were flat, but as the century progressed the waistline moved up to the natural waist and the front of stays curved forward into a funnel shape. By the end of the century the waistline was just under the bust and did not shape the body as it had done decades before – the soft flowing drapery of the gowns did not need stays to provide an architectural function.

I have picked three designs inspired by this century – the first are a fully boned stays from about 1715, a half-boned stitched design from the 1770’s and some transitional stays from 1795.

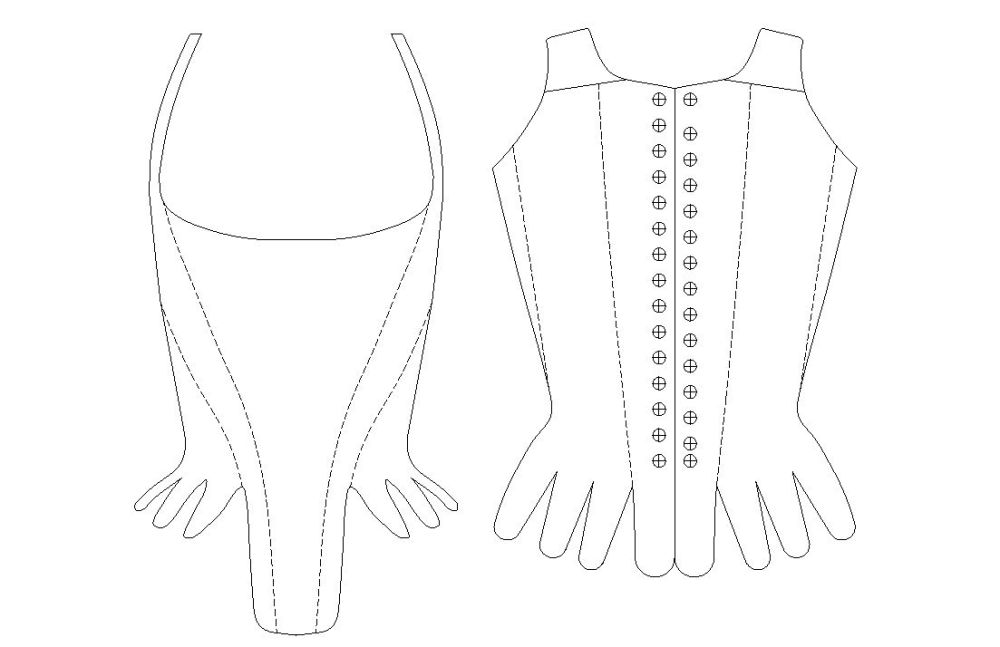

1. Fully-boned Stays 1715 (Baroque)

This design is very typical of the early part of this century – the stays are long at the front with shorter skirts and feature five panels per side plus a strap. The eyelets can be offset for spiral lacing.

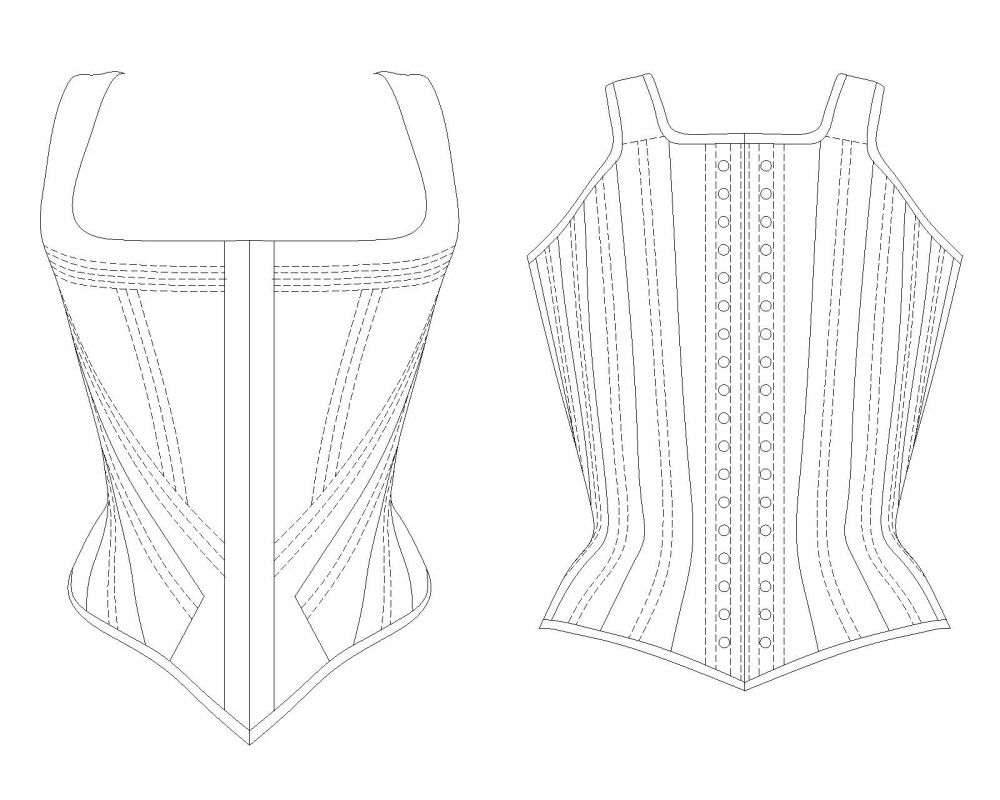

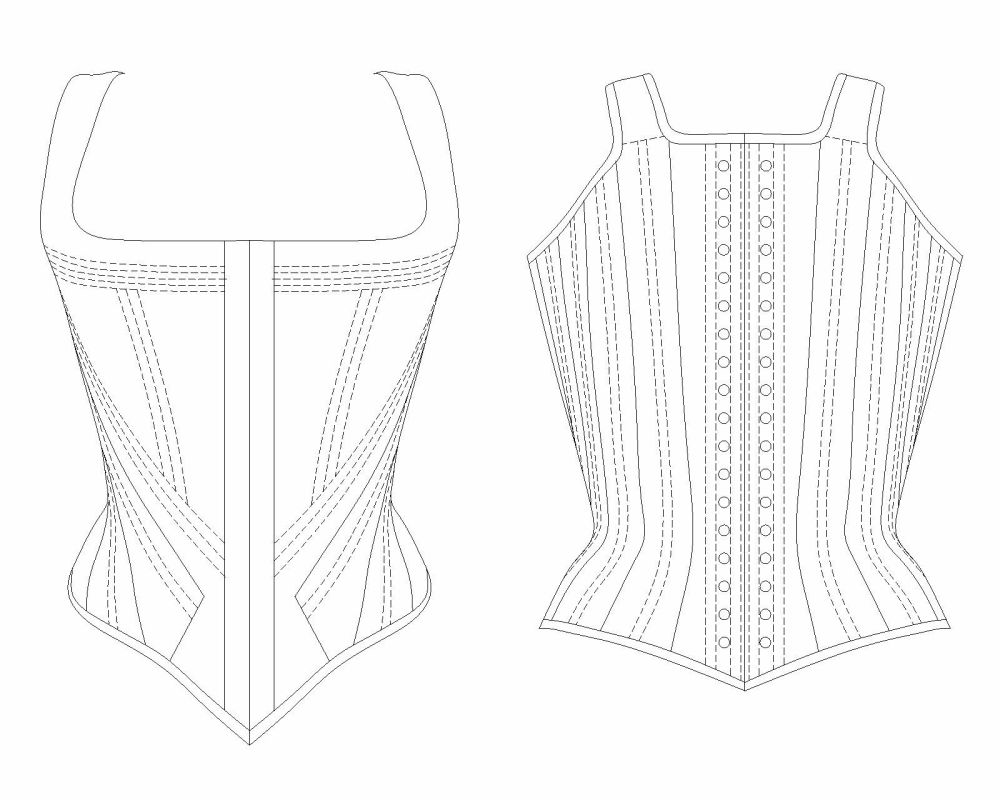

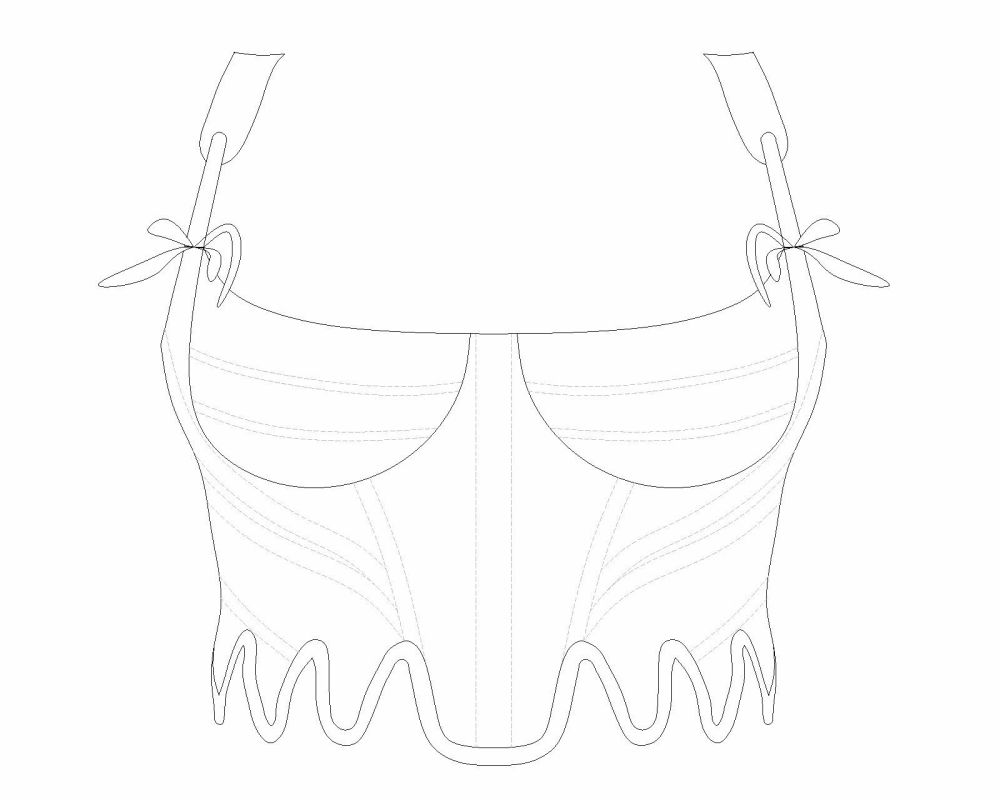

2. Half-boned Stays 1770’s (Rococo)

This pair of Stays housed in the V&A’s collection was the inspiration for this design; Stays | Unknown | V&A Explore The Collections (vam.ac.uk)

This is an example of how inspiration can be taken and changed to something quite different. The following describes the differences of this modern version to how stays were made in the eighteenth century;

- Historically, the skirts (also known as tabs) are separate and splay out over the skirts. These can be made with the skirts fused and shaped over the hip.

- Original stays were usually four panels - the front and back panels are very similar to the V&A example, but the two mid panels are split into six so that if the skirts are left unfused, each skirt tab is an individual panel and can be bound separately with the binding sewn into the seam.

- Historical stays were at least three layers with extra strengthened areas at the belly (often with added paper) and along the waist and top. Rabbit skin glue on canvas and linen strips were used for this purpose. The modern version can be created with no added strength panels. The order of fabric for historically accurate stays are 1) top layer, 2) densely woven thin linen canvas, 3) bones, 4) heavier linen, 5) lining.

- The horizontal channels at the top of the front panel would have been thin strips of whalebone – double corded channels can be used in the modern version.

- A 'bust rail' of metal or whalebone at the top of the front panel was used to give strength and shape – this detail is not part of the pattern.

- The panels in historical stays were whip-stitched together, the front and side front, the back and side back, and then joined at the middle. Each panel would have been boned before being joined together. If using a sewing machine, it is easier to sew the panels together before boning.

- The bones are angled centrally into the skirt tabs on historical corsets. This pattern uses 6mm x 1mm synthetic whalebone more sparingly than would have been used in a pair of half-boned stays.

- Eyelets were ‘awled’ and worked by hand. Eyelets were not worked through the lining - the lining was added afterwards and felled to the stays to enable them to be changed, at a later date, when dirty.

- Lacing of historical stays was of the spiral configuration with offset eyelets at the top and bottom – for a more modern feel they can be laced with the later Victorian/modern configuration with bunny ears at the waist.

- Binding would have been with a wool twill tape or grossgrain ribbon, never bias tape and with the selvedge on the right side /flipped over and stitched to the wrong side. Bias tape can be used on the tricky curved bits, and on-grain tape on the not so tricky bits.

- Historically, a singular wooden busk was sewn into a pocket at the Centre Front (CF) and could be removed. This pattern describes how two standard bones on each side of a zip at the CF can be used as an alternative.

- The lining (linen) was normally added in two main panels with the skirts being lined separately. This pattern describes how lining fabric can be made in three panels per side using the eight panels to redraw a looser lining.

- Historical stays did not have a lacing gap.

- Stays were well steam-pressed into shape – particularly the bust and shoulders where the garment needs to be shaped to follow the body contours.

3. Transitional Stays 1795 (Early Regency)

With the higher waist came a new form of shorter stays that were initially similar shaped to the stays of the eighteenth century, now termed transitional stays, but then developed to give the bust an uplifted and separated profile. The inspiration for this design are the much-admired V&A example that can be seen here; Stays | Unknown | V&A Explore The Collections (vam.ac.uk)

Typical attributes of these stays;

- Often feature a skirt (also known as tabs)

- Minimal to moderate boning

- Mid-diaphragm

- Featured a gathered or gusseted bust

During the late 1790s-early 1800s transitionary period, many women wore stays that hugged the ribcage, pushed up the under-bustline, and created support for the bust without either the actual cups of 1810s-style corsetry or the conical shape of 1780s stays.

The nineteenth century (Regency)

The Regency in the UK was a period at the end of the Georgian era when George III was deemed unfit to rule due to his illness, and his son ruled as prince regent. Upon the Kings death in 1820, the prince regent became George IV. The term Regency (or Regency-era) can refer to various stretches of time; some are longer than the decade of the formal Regency, which lasted from 1811 to 1820. The period from 1795 to 1837, which includes the latter part of George III's reign and the reigns of his sons George IV and William IV, is sometimes regarded as the ‘Long Regency Era’ and characterised by trends in fashion, literature, politics, and culture. In France it began with the French Revolution of 1789 and ended with Queen Victoria's rise to power in 1837. Just prior to this era was the time of American independence (1784); with France and the US being on one side, and Great Britain on the other, there was also often a marked distinction sartorially with the adoption of certain styles happening at slightly different times. The gradual shortening of the corset started in France as a response to the new fashions.

This timeline explains how the fashions changed and historical context of the Regency period at the beginning of the century;

|

Dresses narrower, busts higher, sleeves shorter Square necks came in 1804, also round and heart-shaped 1806 pantalettes and Regency wrap type brassiere Around 1808, the soft gathered gowns gave way to a slimmer and sleeker Regency silhouette. Darted bodices began to appear and hemlines started to rise. Long sleeves and high necklines were worn during the day, while short sleeves and bare necklines were reserved for evening gowns. The sleeves were puffy and gathered, but the overall silhouette remained sleek, with the shoulders narrow. The shape of the corset changed to reflect the looser, draped, shorter waisted style. Between 1808 and 1814, English waistlines lengthened, and decorations were influenced by the Romantic movement and British culture. Dresses began to exhibit decorations that echoed the Gothic, Renaissance, Tudor, and Elizabethan periods. Ruffled edges, Van Dyke lace points, rows of tucks on hems and bodices, and slash puffed sleeves made their appearance. The length of the gown was raised off the ground, so that dainty kid slippers became quite visible. 1809 – horizontally pleated neckline with a band down the middle 1810-1814 waistline lowered a little and then moved higher until its highest point in 1817 Hems rose and dresses cut with more flair with fullness moving around to the back of the dress creating a closer fit over the front and hips of the skirt which became more A-line. A small bustle pad was worn to help create the fullness at the back. Frills and flounces from 1814 |

1811 ‘proper’ Regency begins 1811 Luddite uprisings in response to the industrial revolution 1813 Pride and Prejudice published 1814 steam printing began allowing much faster newspaper printing and the popularity of the fashionable of novel 1815 Napoleon defeated at the Battle of Waterloo 1817 Jane Austin dies

|

|

Waistline fell back to middle of rib cage Fuller wider dresses and fuller petticoats to support the emerging silhouette Very wide horizontal neckline pushing sleeves off the shoulders – ‘leg o’mutton’ sleeves’ Hems padded and decorated |

1818 Frankenstein published (Mary Shelley) 1820 George III died ending the regency |

I have chosen two designs that cover this important period in the history of stays and corsets – the short and long stays;

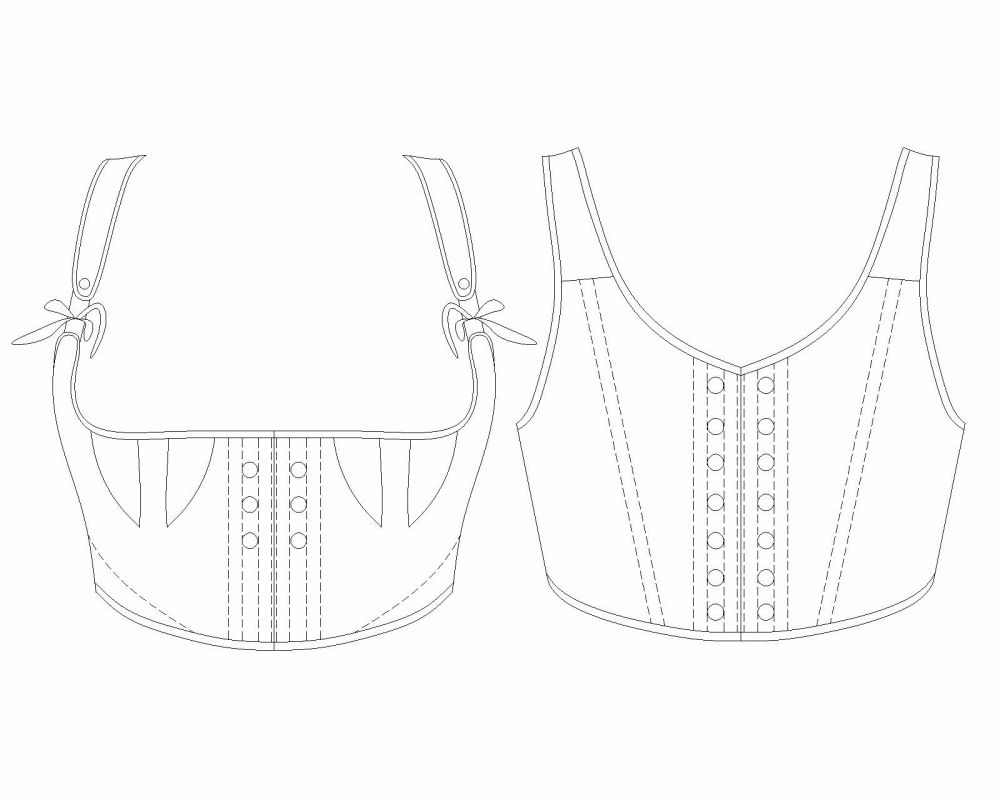

4. Short Regency Stays 1810

Sparsely boned or corded – the half or short stay is the brassière of the nineteenth century. This example uses bust gussets to give that uplifted bust-shelf profile so reminiscent of the time. They feature an (optional) expansion panel at the centre front and cording at the sides.

5. Long Regency Stays 1820

The underpinnings of the later Regency period are unique in that they were not used to shape the torso or waist - it was all about lifting the bust. Whalebone was still part of the architecture but much more sparingly – cording, often used to create beautiful designs, was the strengthening material of choice. This design uses more panelling that would have been used historically, and boning rather than cording, however the panels could be easily corded to be more historically accurate.

The nineteenth century (Victorian)

The Victorian era lasted from 20 June 1837 until Queen Victoria's death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardian period, and its later half overlaps with the first part of the Belle Eproque era in Europe.

There is so much one could discuss about the Victorian era – in relation to corsetry there was the invention of the sewing machine (1846), metal eyelets and the split busk. There was a very rapid development of science, technology and medicine during this period which was used to good effect in respect to inventive means of applying architecture to fashion.

The fashionable silhouette in the Victorian era was very different to the eras already discussed, with the emphasis now very much on a narrow waist.

1830’s

The fashions were extravagant with ballooning sleeves, drooping shoulders, long pointed angles and low pinched-in waist. These low-waisted dresses required long, heavily-boned corsets to give them their shape.

1840’s

The corsets of the 1840s were cut from separate pieces stitched together to give roundness to the bust and shaping over the hips. A broad busk (a flat length of wood or steel) was inserted up the centre front of the corset to give a smooth line to the bodice of the dress. Strips of whalebone were also inserted up the back and sometimes down the side and front, to give more structure. Corsets also had to be rigid to conceal the layers of underwear, including chemise, drawers and petticoat, which were worn underneath.

1850’s

The layers became progressively heavier until the artificial cage crinoline appeared in June 1856 as a welcome and more practical alternative to supporting the skirts. It was made of spring steel hoops, increasing in diameter towards the bottom, suspended on cotton tapes. This design was strong enough to support the skirts and create the desired bell-shaped effect.

1860’s

After 1862 the shape of the crinoline changed from bell-shaped to a flatter front and being projected out behind - bustles gave shape and form to the dress. As the skirts became narrower and flatter in front more emphasis was placed on the waist and hips. A corset was therefore needed which would help mould the body to the desired shape. This was achieved through making them longer and from more separate shaped pieces of fabric than the corsets of the 1840s. To increase rigidity, they were reinforced with whalebone (baleen), or cording or leather.

Steam-moulding also helped create a curvaceous contour. Developed by Edwin Izod in the late 1860s and still used in the 1880s to create elegant corsets, the procedure involved placing a corset, wet with starch, on a steam heated copper torso form until it dried into shape.

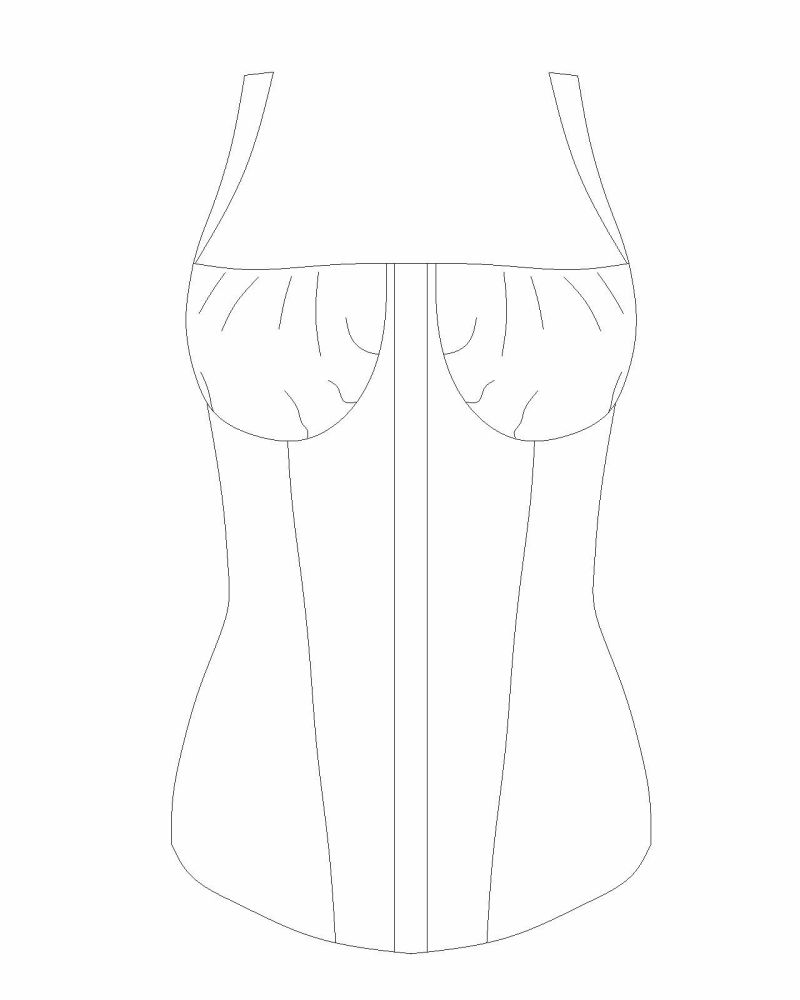

6. Mid Victorian 1860

This corset is all about using gussets for shaping. The inspiration is the Mina Sebille corset patent from 1862 that used quilting to further strengthen the bust and hip areas. US39964A - Improvement in corsets - Google Patents

1870’s

This period was characterised by a sloped bustle style with drapery emphasis at the back, often supported by crinolettes. Development of the 'spoon busk', which was invented in about 1873. Its distinctive shape was heralded as an important innovation, increasing comfort, preserving health, reducing unsightly bulges and enhancing the figure.

A crinolette consisted of rows of fabric-covered steel half-hoops. Bustled dresses of this period had layers of ruffles, pleats, and gathers. Many featured looped overskirts or long bodices that were draped up over the hips and referred to as “polonaise” style dresses.

The second silhouette of the 1870s began around 1876 - the bustle collapsed into the ‘princess line’ style. Named for Alexandra, Princess of Wales, who popularized the look, it consisted of a dress without a horizontal waist seam, fitted instead with long, vertical tucks and darts to create an extremely slim, body-conscious look. Snug around the hips, princess line dresses and cuirass bodices lacked a bustle, with volume instead spilling from below the hips, and sometimes from below the knees. This fullness could extend into long trains, even on day dresses.

The waistline dropped to the natural waist in princess line looks. Additionally, shoulder seams began to creep slowly upwards, and sleeves tightened, further accentuating the long, slim line. Corsets lengthened over the hips to secure the body into the fashionable slim princess silhouette. Additionally, the tightly fitted gowns required less bulky undergarments, and ladies began wearing combinations, a single garment that connected the chemise and drawers. While combinations had been available as early as the late 1850s, they only became common in the 1870s.

The crinoline hid the corset from the waist down so corsets were quite short up until 1870 – they became longer in the 1870’s.

1880’s

The 1880s featured two distinct silhouettes in women’s fashions. The first was marked by the “princess line” and had begun earlier, around 1876. It was a dress without a horizontal waist seam, instead moulded snuggly to the body by vertical seams and tucks, creating a body-hugging silhouette Similarly, this long, slim line could be created with a cuirass bodice, which emerged as early as 1875; it consisted of a long, tightly-fitted bodice, frequently boned, that extended over the hips. The princess line was marked by the continual diminishment of the soft sloping bustle of the early 1870s, until it nearly disappeared for a short time during the early 1880s. Instead, minimal fullness emerged from below the hips, with decoration concentrated low on the back.

The second silhouette of the 1880s began developing around 1883 and disappeared in the 1890s. By 1884, the bustle had returned, this time a hard, shelf-like protrusion that projected from the small of the back. This bustle was rigidly structured, as opposed to the soft, draped bustle of the 1870s. The bustle reached its largest size by 1886, “whereon a good-sized tea tray might be carried,” as one writer commented at the time. After about 1888, the bustle began to slowly shrink in size until 1891, when it gave way to the bell-shaped skirts of the 1890s.

Corsets at this time were shaped to create an hour-glass silhouette – large bust and hips, and small waists. The front often curved over the belly with the aid of spoon busks – gussets and gores helped to create the pronounced curves.

1890’s

The 1890s were a transitional decade from the stiff Victorian Era to a new century. New freedoms and technologies drove an era that became known as the ‘Gay Nineties’.

In the first years of the decade, the silhouette was a continuation of the late 1880s style, with the notable development of a small vertical puff at the shoulder. By 1892, the dramatic, protruding bustle had completely disappeared, and the silhouette most associated with the 1890s took hold. Skirts were bell-shaped, gored to fit smoothly over the hips, and bodices were marked by the large leg-o-mutton or gigot sleeves. The early puff grew greatly in size reaching an apex in 1895. The width at the top and bottom of the silhouette was balanced by a nipped waist, to create an hourglass effect.

Corsets during this decade were lightweight and simply panelled, often with no gores and gussets at all but usually a mix of both shapely seaming and gores. There was a mixture of whalebone and metal boning, and cording was used decoratively. There was often a wide metal bone at the mid-section.

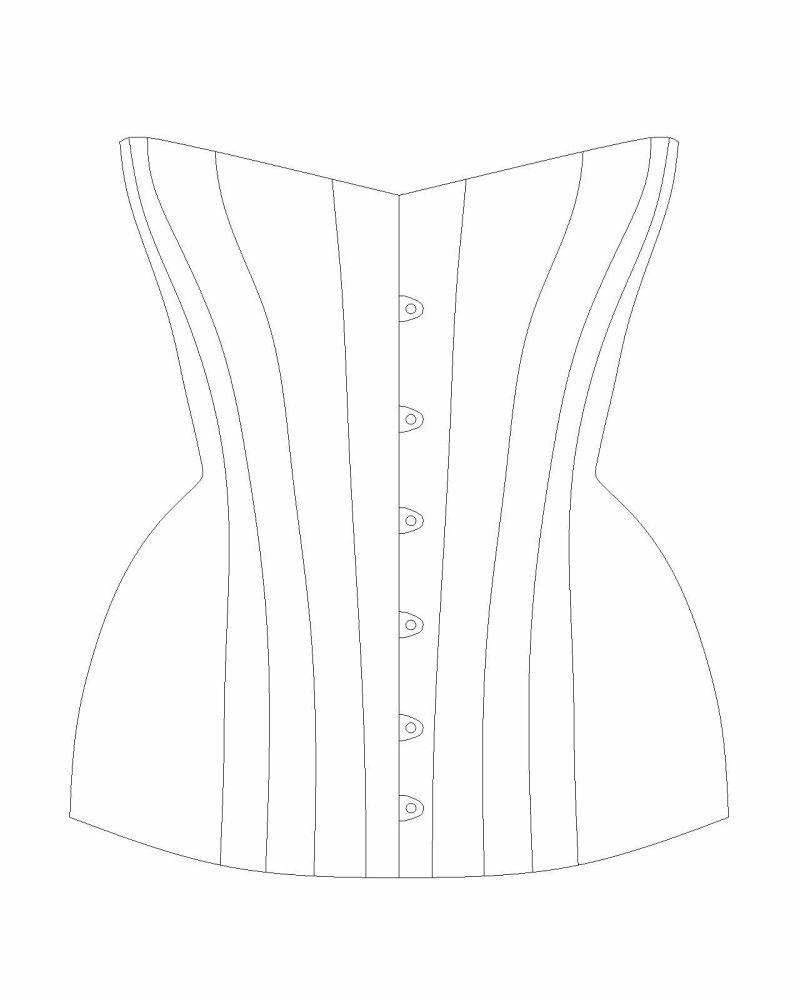

7. Late Victorian 1895 (Ada)

This design was inspired the many Symington pattern designs of this era (available through the Leicestershire Museums website) – it has a low front and is designed for use with a straight busk and worn over a chemise.

The twentieth century (Edwardian through to the Great War)

Around 1897, the silhouette began to slowly shift with the introduction of the straight-front corset. Supposedly designed as a healthier alternative, these new corsets forced a woman’s chest forward and hips backward into a curvilinear “S” shape, that became the dominant silhouette by 1900. The straight-front corset, also known as the swan-bill corset, the S-bend corset, or the health corset, was worn from circa 1900 to the early 1910s.

The straight-front corset was popularized by Dr Gaches-Sarraute, a corsetiere with a degree in medicine. It was intended to be less injurious to wearers' health than other corsets in that it exerted less pressure on the stomach area. Ribbon corsets were also prevalent at this time. As the century progressed the corset became much more about smoothing over the hips – there was a functional aspect as well – suspenders positioned at the bottom of these longer line corsets held stockings up.

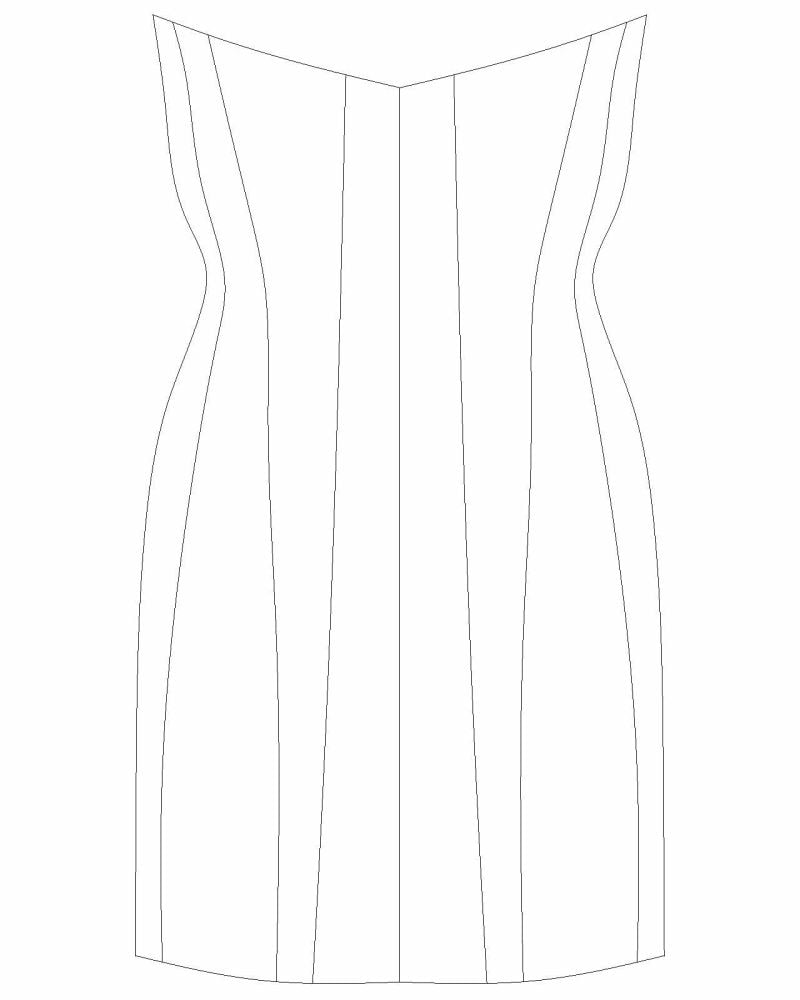

8. Turn of the century ribbon (1900)

There are two versions to this pattern – one can be made with ribbons attached only at the centre front, mid and centre back panels, and there are instructions to make the design with fabric panels that are conventionally sewn together. Instructions are also given to use darts to give that little extra curve over the hip – a modern twist.

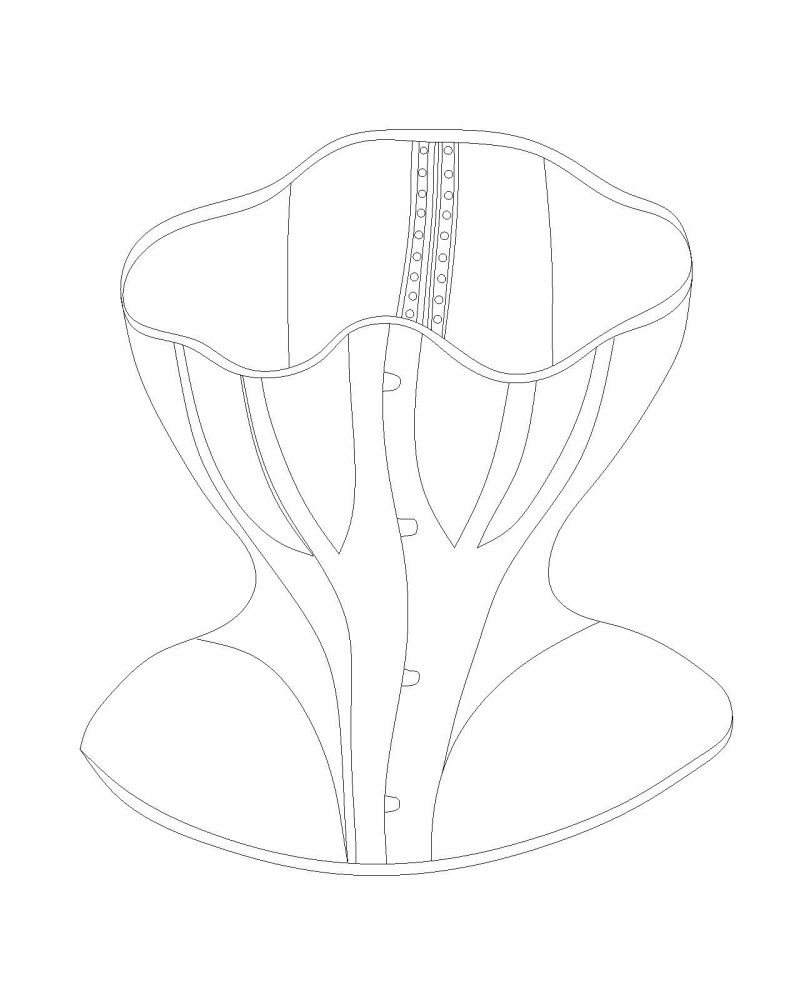

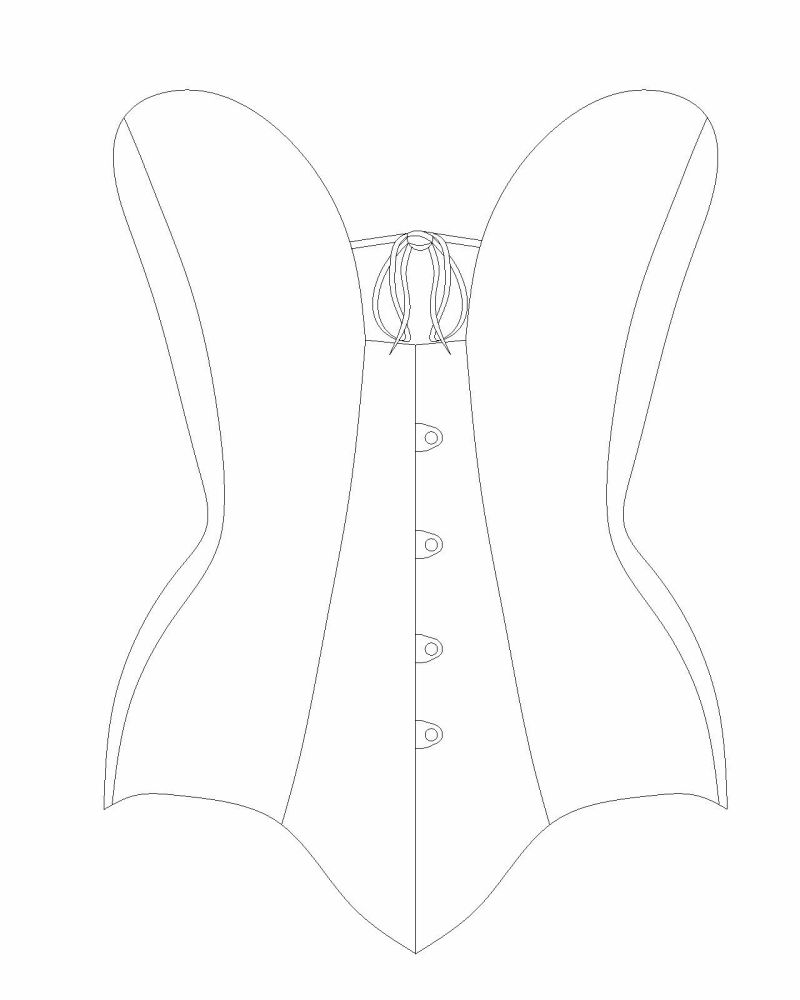

9. Edwardian (1905) – Sanakor-inspired

This beautiful S-bend corset is housed in the Symington collection but is a French design. It has five panels per side and a plunging front with side-front panels that extend to the under-bust.

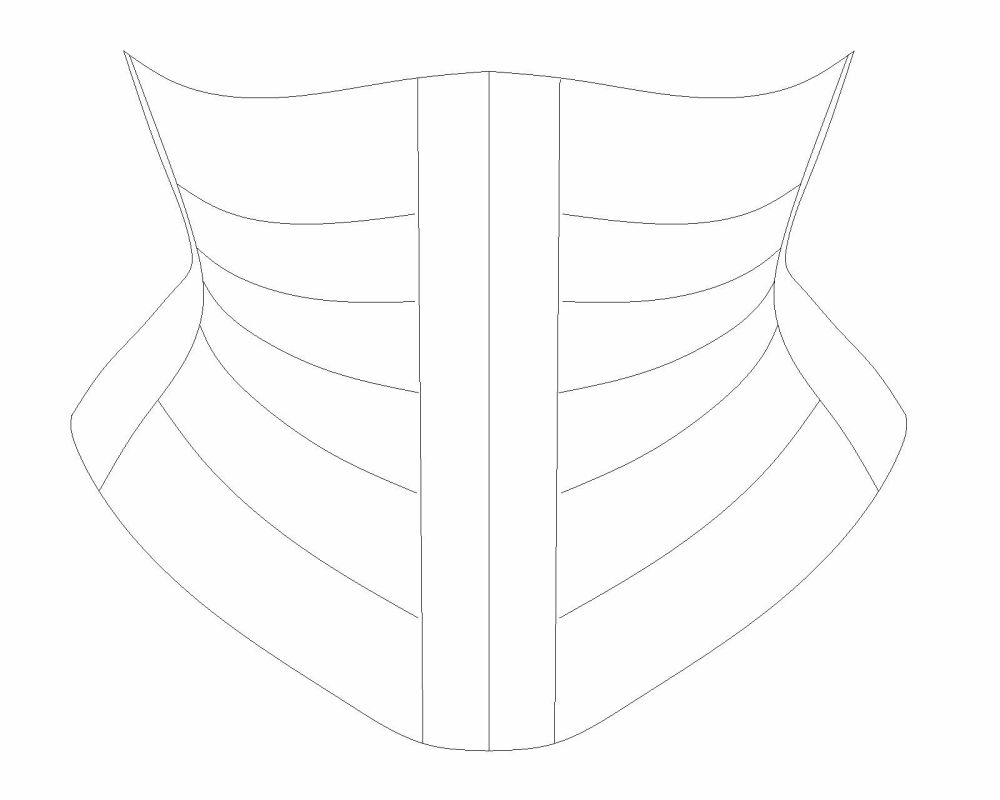

10. 19teens (1915)

The Elizabeth Hume patent was awarded in 1917 but had originally been designed earlier in the first world war. An under-bust of incredible elegance in its patterning, this version is lengthened so it can be worn as a high-waisted skirt.

Summary of the sizes

|

length in |

Imperial |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

CF |

CB |

Bust |

Under-bust |

Waist |

High hip |

||||

|

1715 Stays |

13.4-14 |

15.7 |

29-45 |

26-42 |

21-37 |

Splay to fit |

|||

|

1770's Stays |

13.4-15.3 |

16.5-18 |

31.5-47.5 |

27-43 |

22-38 |

32-48 |

|||

|

1790's Transitional Stays |

7.5 |

8.7 |

- |

27-39 |

- |

- |

|||

|

1800's Short Stays |

4.7-5.7 |

5.9 |

- |

25-39 |

- |

- |

|||

|

1810's Long stays |

16.1 |

16.9 |

31-47 |

28-44 |

24-40 |

30-52 |

|||

|

1860's Corset |

14.5-14.9 |

13.8-14.5 |

26-48 |

25-43 |

22-38 |

33-49 |

|||

|

1895 Corset |

13.4-13.6 |

14.5-15.3 |

28.5-47.5 |

26.5-42.5 |

24-40 |

29-48 |

|||

|

1900 Ribbon Corset |

10.6 |

14.2 |

- |

26-42 |

22-36 |

31-46 |

|||

|

1905 Corset |

15 (10.6@CF) |

12.4 |

- |

26-42 |

19-36 |

31-47 |

|||

|

1915 Corset |

20.9 |

26 |

- |

|

27.5-41.5 |

21-39 |

35-53 |

||

|

length cm |

Metric |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

CF |

CB |

Bust |

Under-bust |

Waist |

High hip |

||||

|

1715 Stays |

34-35.5 |

40 |

74-114 |

66-107 |

53-94 |

Splay to fit |

|||

|

1770's Stays |

34-39 |

42-47 |

80-121 |

69-109 |

56-97 |

81-102 |

|||

|

1790's Transitional Stays |

19 |

22 |

|

69-99 |

- |

- |

|||

|

1800's Short Stays |

12-14.5 |

15 |

|

64-99 |

- |

- |

|||

|

1810's Long stays |

41 |

43 |

79-119 |

71-112 |

61-102 |

76-132 |

|||

|

1860's Corset |

37-38 |

35-37 |

66-121 |

65-109 |

56-97 |

84-125 |

|||

|

1895 Corset |

34-34.5 |

37-39 |

72-121 |

67-108 |

61-102 |

74-102 |

|||

|

1900 Ribbon Corset |

27 |

36 |

- |

66-107 |

56-91 |

79-117 |

|||

|

1905 Corset |

38 (27 @CF) |

31.5 |

- |

66-107 |

48-91 |

79-119 |

|||

|

1915 Corset |

53 |

66 |

- |

|

70-105 |

53-99 |

89-135 |

||