Creating a super-smooth corset with no wrinkling whatsoever is my ultimate aim. This assumes the fit is perfect of course, which goes without saying! How to prevent wrinkling is one of the most common questions asked by novice corset makers, so I thought I'd put a list together that might help anyone new to corset making.

Wrinkles and pulls are stresses or collapses in vertical tension of the fabric – the fabric is resisting the pressure it is under and warps to accommodate. The reasons for this are;

- A panel or boning channel is pulling another panel in a direction opposite to the way the fibres naturally lie – this is especially exacerbated when on the body;

- The grainline is ‘off’ so that when laced down, the fabric is under stress in a direction that causes the fibres to warp to try and mitigate that stress;

- Two or more panels have not been sewn together smoothly with both panels being completely flat or being sewn under pressure (tugging for instance) when underneath the presser foot;

- The panels do not properly contour the body and the body itself creates a pressure on the fibres distorting them;

- There is insufficient boning that causes the fabric to naturally sag into the parts of the body that tend to flex – the waist for example.

To reduce wrinkles there is often a lot of investigation required. I have just realised that I have spent 3 days on just one small area of a corset design – two small seams basically. It often becomes a complete obsession. The changes needed are often ridiculously subtle – sometimes increasing a curve by a couple of millimetres is all it takes. When interrogating, the panels have to be sewn together time and time again and tried on to create the pressure required to see how they react to the changes made. Version control is so important – to my peril I have not been able to find a juxtaposition of panels that worked because I didn’t mark it properly. My process is to make a change to one side, try it on, make changes to the pattern and then make up the other side, comparing and contrasting as I go, and then so on. It is such a long process sometimes, especially with complex designs.

Once the pattern is presented to another maker, a different body and a different sewer is introduced. Does that maker realise how subtle it all is and that sewing that curve off by 2 or 3mm will create problems? Not always, and this is why there are always issues, problems, concerns and hair-tearing moments in this craft that we love.

To reduce wrinkles as a maker, here are some tips;

1. Mark the seam on the fabric with a narrow marker and sew bang on this line to ensure accuracy – this will ensure the pattern is properly followed;

2. Never tug the fabric as you are sewing – let it glide through the presser foot consistently and evenly;

3. If you are sewing a convex to a concave curve that is highly curved and awkward, initially sew a running stitch 1mm from the sewing line (within the seam allowance) on both panels – this stabilises the fibres a little and prevent bias stretch as you sew. Ensure both panels are exactly matched at the waist and then, without pinning, sew on the sewing line (just inside the running stitch) from the waist to the bottom, easing the two panels together. Then sew from the waist to the top in the same way with the same panel on the top as you sewed in the first instance. Ensure when you sew the second side of the corset that the same panel is on top so that you will ensure a symmetry on both sides. If the two panels are quite short, start form the top and sew directly to the bottom. This video might explain this a bit better;

https://youtu.be/ayaZjkp1920

4. Ensure grainline accuracy – parallel tug lines are a good indicator of grainline inaccuracies. Pulling the fabric in a particular direction that smooths them is often the direction the grainline should be tilted.

5. Ensure vertical tension to the bones – the bones should not be able to move up or down in their channels. Flossing helps to secure them and ensure the fabric remains taught (just the right amount of taughtness though – they can be too tight).

6. Grade or clip seams to reduce bulk and to ensure the seam is not creating tension, particularly on really curvy seams. If you have stitched the panels with a tiny stitch, cutting back the seam to 5mm is not normally an issue.

7. Use good quality coutil – flimsy fabric may not be up to the job.

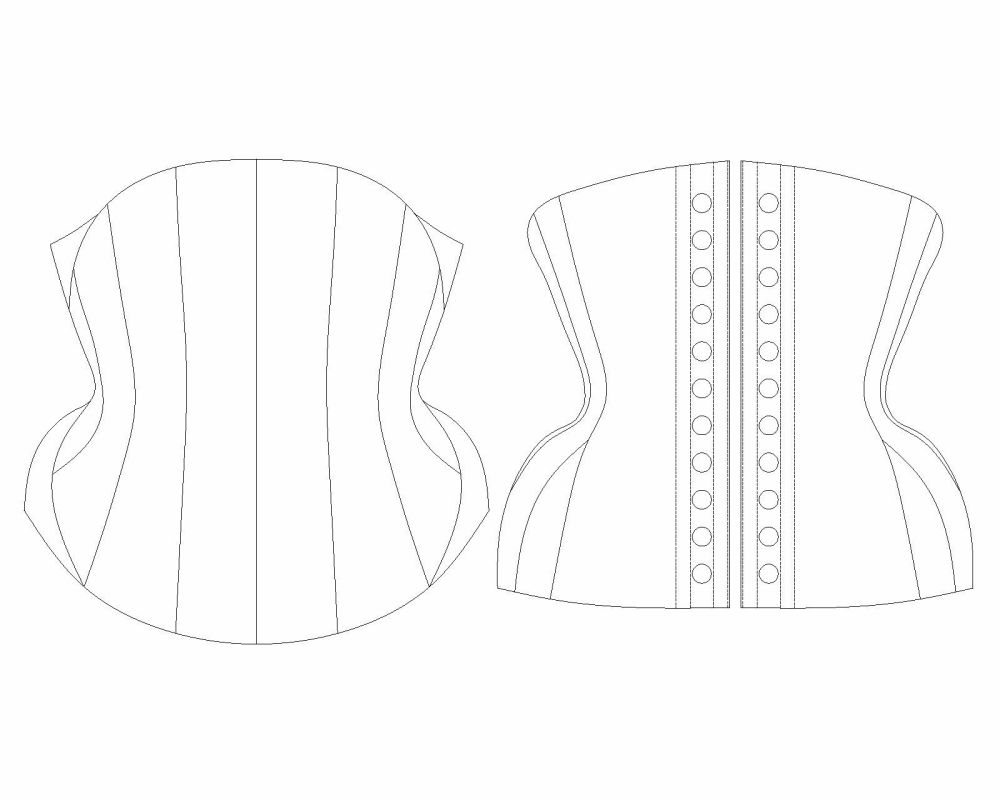

8. Curve the centre back so that fabric doesn’t ‘pool’ in the small of the back, often an area prone to wrinkling.

9. Add in a little ease if you feel the fabric is under pressure, particularly in the hip area – just a few millimetres is all it might take.